Listen to V. Vale talk about Burroughs and the book on the Live! From City Lights podcast.

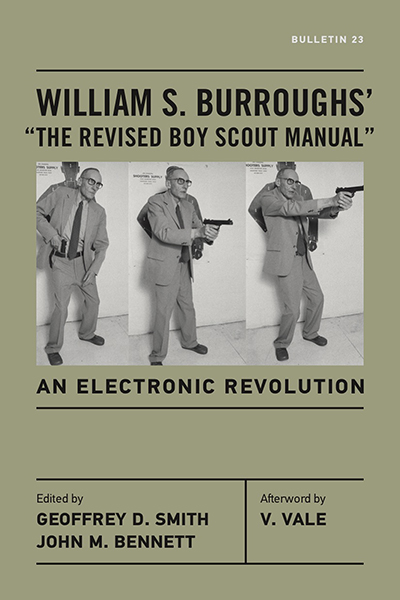

“Burroughs’s jarringly piecemeal satire on how to prepare for a revolution against powerful, oppressive institutions is strikingly timely.” —Publishers Weekly

“A carefully annotated, definitive edition of a long-lost William S. Burroughs work, The Revised Boy Scout Manual is a scathingly humorous, often uncannily prescient guide to revolution.”—Foreword

“It’s all there all the time with Burroughs.”—Marc Maron

“He’s up there with the pope . . . you can’t revere him enough . . . he’s the greatest mind of our times.”— Patti Smith

“The most important writer to emerge since the Second World War.”—J.G. Ballard

“Well, he’s a writer.”—Samuel Beckett

“The Revised Boy Scout Manual offers easy-to-read proof that the uncensored human imagination allowed to freely extrapolate about future social change can offer outrageous scenarios and fresh language capable of inspiring readers decades into the future.”—V. Vale, founder and publisher of RE/Search

“Here we have Bill Burroughs’ voice coming through loud and clear, like a conversation after his first large whiskey, London c1972. His preoccupations at the time: weaponry, viruses, tape recorder cut-ups, Scientology techniques, the Mayan calendar and Korzybski’s General Semantics are utilized as means to deal with ‘the shits.’ Never has a text been more apposite. As usual his ideas are developed into hilarious routines but at heart he is deadly serious: ‘I mean every word I say.’ It is wonderful to see this legendary text in print at last.”—Barry Miles, author of Call Me Burroughs; The Beat Hotel, Ginsberg Burroughs and Corso in Paris 1957-1963; William Burroughs, El Hombre Invisible

Before the era of fake news and anti-fascists, William S. Burroughs wrote about preparing for revolution and confronting institutionalized power. In this work, Burroughs’ parody becomes a set of rationales and instructions for destabilizing the state and overthrowing an oppressive and corrupt government. As with much of Burroughs’ work, it is hard to say if it is serious or purely satire. The work is funny, horrifying, and eerily prescient, especially concerning the use of language and social media to undermine institutions.

The Revised Boy Scout Manual was a work Burroughs revisited many times, but which has never before been published in its complete form. Based primarily on recordings of a performance of the complete piece found in the archives at the OSU libraries, as well as various incomplete versions of the typescript found at Arizona State University and the New York Public Library archives, this lost masterpiece of satiric subversion is finally available in its entirety.

William S. Burroughs was a primary figure of the Beat Generation who wrote in the postmodern paranoid fiction genre. Jack Kerouac called Burroughs the “greatest satirical writer since Jonathan Swift,” while Norman Mailer declared him “the only American writer who may be conceivably possessed by genius.” While he is best known for the novels Naked Lunch, Queer, and Junkie, he also collaborated with artists such as Laurie Anderson, Tom Waits, Nick Cave, Gus Van Sant, David Cronenberg, and Sonic Youth to produce films, music, and performance pieces.

Geoffrey D. Smith is Professor Emeritus, former head of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Library of The Ohio State University Libraries, and adjunct professor in the Department of English. He was also longtime steward of the William S. Burroughs Collection at Ohio State.

John M. Bennett is the founding curator of the Avant Writing Collection at The Ohio State University Libraries. He was editor of the international literary journal Lost and Found Times from 1975 to 2005 and is the publisher of Luna Bisonte Prods, promoting avant literatures since 1974.

V. Vale is a counterculture writer and publisher and the sole proprietor/founder of RE/Search Publications. He published part of Burroughs’ “The Revised Boy Scout Manual” in 1982 in RE/Search #4/5: William S. Burroughs, Brion Gysin, and Throbbing Gristle.

Antonio García is a visual artist, scholar, and philologist studying William S. Burroughs’ work as a process-based art form.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Foreword

Antonio Bonome

Brief Textual History

Geoffrey D. Smith

Did Burroughs Have a Plan?

John M. Bennett

“The Revised Boy Scout Manual”: An Electronic Revolution

Afterword

V. Vale

Supplements

Abbreviations and Sources

Notes

Afterword by V. Vale

It was a huge relief—like releasing a sigh that began in 1981—to receive the news that the complete William S. Burroughs “The Revised Boy Scout Manual”: An Electronic Revolution is being published by an academic press, fully annotated to the nth degree as only professionals can do. The reason for my intense interest is that my tiny publishing company, RE/Search, had planned to publish the full version from 1981 to 1982. Due to a personal relationship blowup and more, the project died on the vine. But not before we had enlisted the highly talented (and now deceased) Osborn brothers (Jim and Dan) to illustrate the book with handmade drawings. A few illustrations were made (I am still searching for them, hoping they can be found), but I went on to other projects. I managed to publish only the first part of The Revised Boy Scout Manual in my RE/Search issue #4/5. Now, having just reread the manuscript, I fervently wish RE/Search could have published it in its entirety in 1982—in all its mind-bendingly prophetic, visionary, inspiring, imaginative, and, above all, incendiary glory. Whew! I would think twice about being seen reading this book on an airplane, much less trying to sneak it aboard in a carry-on suitcase.

I have a theory that friends are BORN, not “made.” And the quick shortcut to establishing a friendship with William S. Burroughs (who was decades older than I) was, as Goethe put it, shared affinities. In our case, these included hatred of authority/authoritarianism, love of solitude, and a passion for scientific knowledge of the deepest human proclivities. Therefore, we each embodied a fierce desire for independence, paranoia of one’s fellow man, and, as a result, a primary passion for knowledge about self-defense and preemptive survivalist behavior—that is, see everybody before they see you! We had a mutual cosmic contempt for the status quo, antiquated language, “beliefs,” economic “systems,” and visual “culture” that now hold an entire planet hostage.

In our passion to learn everything possible about self-defense, we shared a love of guns and a desire to keep abreast of the state-of-the-art refinements continually being innovated by the highly competitive firearms manufacturers. Our quests for information on this subject were granular. One of the big thrills of my life was meeting Uziel Gal, inventor of the “Uzi” submachine gun, at a Bay Area Gun Show. And it was a big thrill when I was able to take a photo of William at the San Francisco Gun Exchange holding a semiautomatic (not full-auto) version of the fabled Uzi machine pistol. Both of us harbored doubts about the efficacy of the 95-grain 9mm round versus the 230-grain .45 cartridge—which was purportedly invented to “neutralize” the drug-crazed “Amoks” allegedly populating the eastern half of planet Earth. But we both agreed that the Government Model .45 automatic, carried by hundreds of thousands of U.S. soldiers during World War II and the Korean War, was almost impossible to shoot with any accuracy (although an exceptional marksman such as Mark Pauline was able to place most rounds within the bull’s-eye at five yards—even usually at fifteen yards.) Then again, we knew that about 99 percent of all self-defense pistol deployment takes place under five yards, with most under a scary eight feet! And we were aware that in one second, an experienced San Quentin ex-con can cover those eight feet and take your self-defense pistol away from you—all the academic training you’ve obsessively endured out the window, just as all the arduous gym workouts building up cosmetically admirable musculature can instantly be nullified by an experienced street fighter who’s spent half his life in and out of prison! We both knew that you never fire a pistol at an attacker once; no, you immediately fire two shots in the “center mass” (chest area) and a third to the head, then back up and prepare to shoot again repeatedly. Some criminals are superhuman in their strength, fortitude, and speed.

These were exact topics we discussed, and much more. Early on, William presented me with the gift of a Cobra, which is a steel handle that, with the flick of a wrist, telescopes into a sharp-tipped metal “rod” capable of breaking flesh and then some. In 1984 I took it with me on a trip to Spain, and the Spanish customs officer frowned heavily but in the end allowed me to take it in my checked luggage. William himself had flown with it; as he put it, “You need three lines of defense. I have a knife, the Cobra, and my cane.” When I visited William in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1988, he showed me an illustrated hardback book titled Cane Fighting. He also gave me knife-throwing lessons against the shack where he stored some of his shotgun paintings. There I found a discarded spray-paint canister bearing multiple colors and asked if I could have it—and would he autograph it? To this day, this is one of my most cherished possessions; I store it in a drawer away from light and moisture.

It’s well known that William S. Burroughs is the éminence grise of countercultural thinking, conceptualizing, exploring, and social experimentation, as well as an early adopter of experiencing. Ayahuasca vision-questing is enjoying a revival now, but he investigated it in the fifties and had his reports published in a 1963 City Lights chapbook titled The Yage Letters. Burroughs invented the term Heavy Metal, which is an enduring subgenre of rock ’n’ roll. He coined the term Soft Machine, which was adopted by an avant rock band whose important members recently passed away. Surely William S. Burroughs was the first person to write the phrase “fake news,” which now rules the professional media worldwide—in this very book, The Revised Boy Scout Manual. In 1970 he had visualized and described a whole variety of memes that could change the world’s hierarchical power structures, using lowly and democratically available audio and video recorders. Currently there are almost a billion smartphones capable of making and sending meme videos and audio recordings all over the world, instantaneously.

The Revised Boy Scout Manual offers easy-to-read proof that the uncensored human imagination, when allowed to freely extrapolate about future social change, can offer outrageous scenarios and fresh language capable of inspiring readers decades into the future. Who can ever forget the crowd chanting “Bugger the Queen!” The darkest possible humor, not shying away from racial and sexual taboos, can be found within the pages of RBSM. Contradiction, the true foundation of our existence, is also evident: early on, William gives scenarios for ridding the earth of the 10 percent who are “shits” ruining our world. . . . Later on he reckons that those who actually kill these 10 percent might well end up turning into “new” versions of them. As William discovered, much to his sorrow, if you kill somebody, your life will be irrevocably changed, and your dream life will be forever haunted and transformed into the stuff of nightmares. One of the best columns of the Police Marksman (a slick color magazine) dealt with stories of officers who have killed criminals and then began suffering excruciating nightmares and PTSD-type traumas that begin ruining their lives and marriages and rendering them incapable of employment.

When I met William in 1981, I got the feeling that there was nobody in his life who shared his love and knowledge of firearms. So right away, I organized a trip to Chabot Gun Club in Castro Valley with a few close friends who, like me, shared what at the time was a most secret passion. The local television station KQED sent a camera team to record our little “adventure.” In a short time William got to try a whole range of firearms he had read about but had never actually been able to handle and shoot. He loudly disdained the use of earplugs, and I foolishly imitated him; it took about a year for the ringing in my ears to fade away. Later on I noticed that he used large hearing-protection headsets. I brought along my recently purchased guns: a Bernardelli .25 small automatic, and the then-heavily-promoted Heckler and Koch P7. When William shot with each of them, they both jammed. I remember his yelling after one of the jams, “Get rid of it! Get rid of it! If a gun doesn’t fire, it’s worthless—it’s just a club!”. So right after the shoot, my friend M , who owned a car, took both guns to a gun store down the peninsula and sold them for cash. Nothing like learning from experience!

Having tracked down and read (or tried to read) almost every book that William ever recommended, I can probably with some validity describe him as a “mentor” of mine. The first time I recall seeing him give a bona fide smile was early on when I took him for breakfast to Mama’s Restaurant in North Beach on the edge of Washington Square Park. At the end of the meal when we were ready to leave, I picked up the check and refused to take his money. He was genuinely surprised, and I got a real smile, not a feigned one. That smile is one of my favorite memories of the man whom I’m convinced will still be read a hundred years from now (if the world lasts that long). Real writers offer you a host of ideas—especially ideas having to do with future freedoms—and if your ideas are futuristic-black-humor-and-speculative-libratory, then . . .

I argue that William S. Burroughs was the preeminent prophet of the 20th century, and his entire opus offers testimony as to the bewildering, dazzling scope of his radical thinking and imagination, with some of the funniest dialogue that has ever been written. If you are a prophet, expect your books to be read long after your physical body is dead. Because, arguably, your words are YOU, and if your language lives on, in a way you live on. What could be better?

—V. Vale, RE/Search sole proprietor/founder, San Francisco, November 29, 2017

Related Titles:

Everything Lost: The Latin American Notebook of William S. Burroughs, Revised Edition

Edited by Oliver Harris, Geoffrey D. Smith, and John M. Bennett

Narrating Demons, Transformative Texts

Rereading Genius in Mid-Century Modern Fictional Memoir

DANIEL T. O’HARA